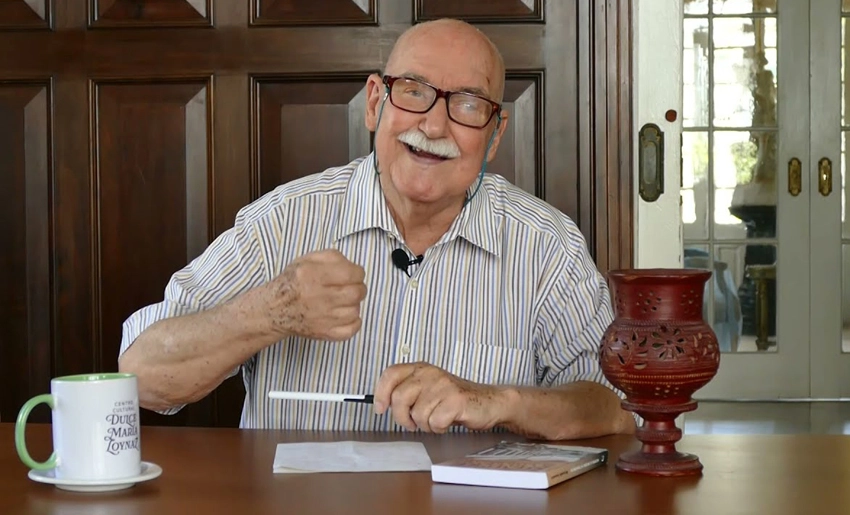

There are so many literary lives of Reynaldo Gonzalez (Ciego de Avila, 1940, National Literature Award 2003), that one never knows where to start, whether from the harvest or from the heart. And the fact is that both conditions -the use of days and the tenacity of his efforts- are his vital path: A diligent narrator -Siempre la muerte, su paso breve (1968)-; a prolific researcher -La fiesta de los tiburones, (1978)-; a rooted essayist -Contradanzas y latigazos (1983)-; a seductive prose writer -El Bello Habano (1998)-; a prize-winning novelist -Al cielo de los tiburones, (1978)-; and a seductive prose writer -El Bello Habano (1998)-; a laureate novelist -Al cielo sometidos, Italo Calvino Award (2000)-; rigorous cinephile -Cuban Cinema, that eye that watches us, (2002)-; elegant poet -Envidia de Adriano, (2003)-; and infinite criollo -El más humano de los autores, (2009)-; are examples that enhance him.

Fifty-four years ago, in what would be Jose Lezama Lima’s last book of essays, La cantidad hechizada (The bewitched quantity), it was noted on its flaps: “When we expect a usual essayistic interpretation, we get caught by another very peculiar one, the one that penetrates and runs through us as it crosses a theme and discovers in us a poetic intuition (…) We are on the threshold of a book where every page, paragraph or word is a possibility of surprise”. All this acquires similar value for a book of high-flying and stately insight: Insolencias del barroco (2010, first in Ediciones Holguin, and in 2013 in Ediciones Cumbres, Madrid, from the original edition), written by the author of those words, the Lezamian editor Reynaldo Gonzalez.

Through five essays written on different dates, in connection with exhibition catalogs or other requests, we have a book that delves into a fabulous area of the 17th century; themes that refer to protagonists and moments, as unique as they are revealing, rooted in an artistic condition that, beyond well-defined themes, shows that impudent character alluded to in the title and that, in addition, becomes the watchword for a personal journey into the Baroque and its entrails. Such a journey is based on the poetic intuition that lies at the very root of the gaze, in the ability to examine what concerns a painter and his work, and with it a never-fixed period frame, always subject to the most unexpected eventualities.

This is how each one of the essays that make up Insolencias del barroco, while traces of character and circumstances, are also fragments of choral image: impertinence of similar pictorial modes in terms of vocation, indocility, prerogative, derivation, that Reynaldo Gonzalez proposes as uncommon models of the baroque and, singularly, from themselves, as a ubiquitous figure that illustrates their natural disobedience. And the fact is that each of them proposes an event: Money, brushes, crucifixes, for example, is a sample of the reciprocities between greed, profit and usufruct through paintings that, wrapped in a cunning exchange of the human and the divine, capture the interiorities of an era and its relationship with art.

Other samples of excellence are Las sinrazones de Piranesi, on the sensibility of the famous Venetian engraver, noting his qualities to delve into antiquity and, from that fact, rather than formulating an order, lead to the knowledge of his chimeras -and it is worth remembering the great author of Memoirs of Hadrian, Marguerite Yourcenar, when she asserted that “the genius of the Baroque gave Piranesi the intuition of that pre-baroque architecture that was imperial Rome”-; and El tenebrismo: The insolence of art, a journey between light and shadow through the passages of Orazio and Artemisia Gentileschi, his master Caravaggio, and his later disciple, José de Ribera, a journey that is affirmed in the characters of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s films.

In the two final essays, the taste for exploring the labyrinths of the work of such venerable brushes acquires a verbal refulgence worthy of the paintings: The divine androgynous divine, proposes a reading of human beauty subject to the everyday, installed in the mythical and vice versa, from Greece and Rome to the baroque plenitudes, always betting on the contingencies of the artist and his environment when it comes to transfer naturalness, risk and daring; and in Velázquez, a court seen by a paintbrush, a family portrait, and in this case Las Meninas has its main attribution in the demarcation of circumstantial lines, without forgetting the subtleties -which can be seen in the framework and its characters- of the artist and his time.

Whoever delves into the pages of Insolencias del barroco is witnessing an encounter that entails a double enjoyment: on the one hand the writing, smooth and delightful -the pleasure of the essay that knows how to narrate, illustrate, think, confront-, and on the other the inquiry, meticulous and tempting, both interwoven in favor of the most fortunate reflection, which does not give way to boasting, but rather to sympathy, remembering that, as the Mexican writer Octavio Paz said, “without it there can be neither understanding of the work nor judgment on it”. To which we can add the fact of a persuasive will that is explored in each one of these essays, tasteful in the intimate and in the common, to make possible that the reading also derives in adventure to be grateful for.

A book about some exciting coordinates of art and its most unforeseen moments at the time of the spell: in it converge the hedonistic passion of the initiated, and the punctual review of the connoisseur; the qualities of the tasteful telling are not at odds here with the skills of the judicious deciphering. This is a book that also invites us to reread other pages of his -and in that sense, it would be worthwhile to take a look at his novel Al cielo sometidos, which in many sections shows some of these “insolences”-. An invitation to painting from the word that unravels it, based on the pleasures of the good look, thanks to the rigor of the essayist and the splendor of the novelist that concur there: Reynaldo Gonzalez and the insolences of the baroque prove it.

- Maggie Mateo returns as a storyteller - 21 de May de 2025

- Farewell to Mario, Don Miguel’s disciple - 16 de April de 2025

- The savage detective and the unsubmissive translator - 7 de April de 2025