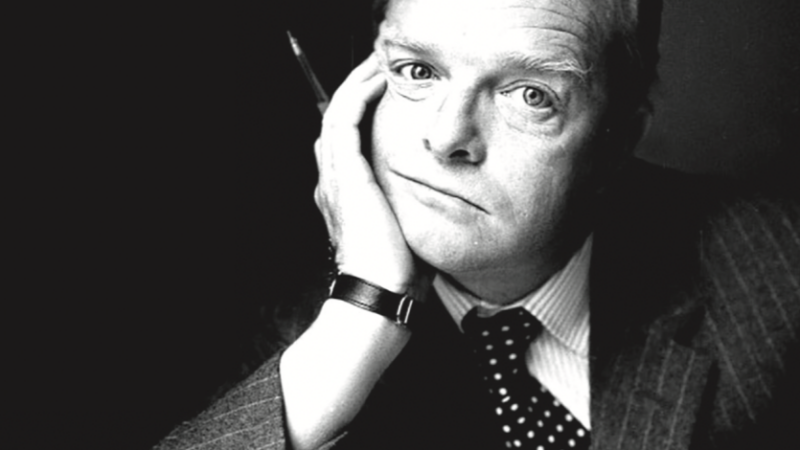

“He is the most perfect writer of my generation.” Norman Mailer once wrote, judging the literary work of Truman Capote. When he died in 1984, he had been working for almost 20 years on what would become his masterpiece: Answered Prayers. He was 60 years old at the time, and some claim that the true cause of his death was an acute case of writer’s block. That is, his inability to complete the most famous unpublished novel in contemporary American fiction.

From a fleeting union between a traveling salesman and a beautiful college student. Who separated a few months after getting married. A son was born, whom they named Truman Persons. He would later be adopted by his mother’s second husband, of Cuban origin. So his surname was soon changed to Capote, not Persons.

At a very young age, he established himself as one of the writers of the New Yorker magazine. Which brought together professionals involved in the new post-war American literary trends. J.D. Salinger (The Catcher in the Wheatfield) and John Updike (The Rabbit Returns). In this publication, he managed to publish some texts that allowed him to live decently for a time.

In 1976, three chapters of his novel Answered Prayers were published in Esquire magazine, causing a great stir. Capote claimed that his intention was to write a modern-day equivalent of Proust’s In Search of Lost Time. To do so, he described the European and North American aristocratic world. An environment he knew very well given his friendship with some of its most famous members. Many of them appear barely disguised and in some cases with their own names.

Almost all of them ostracized him, leading Capote to indignantly comment: “I don’t know why they were so angry. Who did they think they had among them, a palace jester? They had a writer.” And a narrator whose work cannot be elegantly summarized. As his style varies constantly, although his style is precisely one of his greatest achievements.

Born in New Orleans in 1924, he began writing, he says, before the age of 10. He achieved fame before the age of 20, when he published his first stories. At 19, he won the O’Henry Prize for the title Miriam. Which he considered a clever trick and nothing more. In 1949, at the age of 24, his first novel, Other Voices, Other Spaces, appeared. In it, he developed some of the typical mannerisms of Southern American literature and was very well received by critics and the public.

His short stories and novels already place him among the great writers of the momento. Moreover which is possible, as Capote declared, since “I am a great admirer of Faulkner, Eudora Welty, Flannery O’Connor, and Carson McCullers.” Although he soon stopped considering himself a regionalist writer and said: “My first book was set in the South simply because that was what I knew most intimately at the time.” He acknowledged that his great masters were Flaubert, Maupassant, and Proust.

Clearly, he wasn’t lying when he stated years later: “The South long ago ceased to provide me with plots for my books.” His 1958 novel, Breakfast at Tiffany’s, where preciousness gives way to social curiosity, is set in New York. It concludes one of the cycles of his work, which until then consisted of short stories—some masterful—comedies—of little success—film scripts—failed—and reports—which all contributed to making him a figure of great fame.

Aside from being a talented professional, Capote was a public curiosity. An eccentric figure due to his lifestyle and his reputation for saying scandalous things. He once declared on television: “I am an alcoholic, a drug addict, and a homosexual.”

In 1966, his work In Cold Blood appeared, in which he addressed a crime that filled American public opinion with horror. To write it, Capote spent three years between state prison and the small Kansas city where the murder took place.

The result is a fictionalized reportage, or as he himself explained: “a book that I try to have the credibility of the facts. The immediacy of cinema, the depth and freedom of prose, and the precision of poetry.” It is, in fact, a shocking testimony. This book combines literature and events from an era dominated by surrealism.

When he died, his editor, biographer, and lawyer carefully reviewed all the pages the writer had left behind in various homes. Regarding Answered Prayers, they only found the chapters published in Esquire and a few notes. There is no trace of any of the other chapters he had mentioned to his editor and even read to some friends.

Regarding this event, hypotheses run wild. On one hand, there are those who believe the complete manuscript is kept in a safe deposit box. Others say the original is hidden by a former lover. But his editor, Joseph M. Fox, author of the prologue, shares none of these assumptions. Nor does he share the claim that Capote only wrote three chapters and, because the reaction from his friends was so terrible, he didn’t continue.

Fox is inclined to think rather that Capote concluded that what he had written was beneath Proust. A standard he had set to surpass in his novel.

All this caused a crisis that altered his conception of writing. He never fully recovered. He failed to find and utilize all the resources he had learned in film scripts, comedies, reports, poetry, short stories, and novels. A writer should have all his colors and abilities available on the same palette to blend and, in appropriate cases, to apply them simultaneously, but how? He must not have found the answer, and since, as he said, he not only sought to write well but also to create authentic art. In Answered Prayers he may have attempted to elevate gossip to the level of art.

Despite this, the book’s nearly 180 pages reveal an uneven writing style. With great expressive insights and very sharp observations about figures such as Jackie Kennedy, Greta Garbo, and Andy Warhol. Among other prominent figures in literature, the arts, politics, journalism, and the aristocracy of his time.

Translated by Aliani Rojas Fernandez

- Happiness, Appreciating What You Have - 6 de February de 2026

- When eating pizza doesn’t lead to Rome - 18 de January de 2026

- The Fright of Tuesday 13th: Between Religion, History, and Tradition - 13 de January de 2026