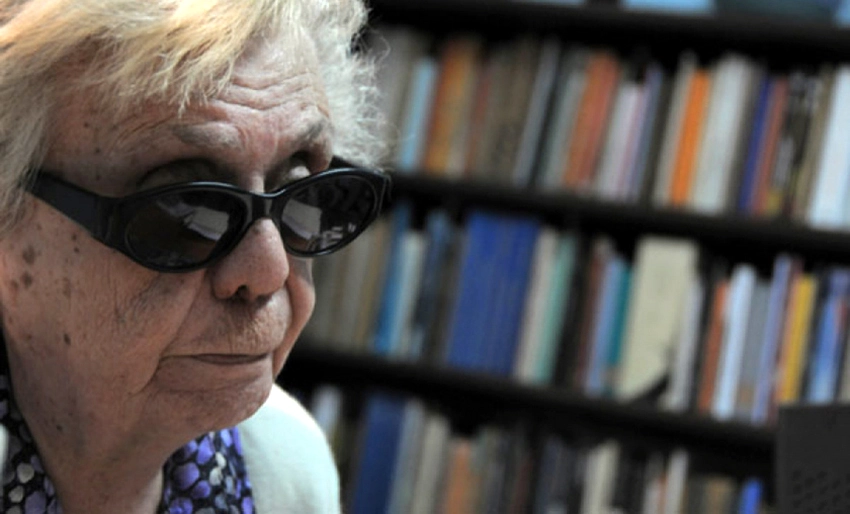

Nonagenarian who keeps her intellectual capacity attentive, her life has passed in the pointer of culture; with respect and affection they call her “La Doctora”, not only for her academic degree, but with the sum and adequate elegance of knowing that, with such a title, she is the first in the arts in the island: Graziella was born on January 24, 1932 in Paris, daughter of the great Cuban painter Marcelo Pogolotti, and in her the sharpness with more than enough and the curiosity without fainting are santo and sign.

As an essayist who walks with flair through the most dissimilar fields when it comes to sagacious texts -literature, drama, painting, testimonial remembrance…-, among the possibilities that Graziella has taken forward when it comes to writing, there is one that is rarely highlighted, in the face of the most marked trace of her steps through literary and artistic criticism: I am referring to the prologue -as if it were a matter of conversing with the utmost kindness and understanding-, a punctual invitation to the encounter with a work of art.

“I have always thought that on a desert island, in the secluded retreat that will be my lot once I have done my small part in the hard work of these years, I would aspire to have at hand a copy of The Charterhouse of Parma. A solid and heavy edition, in large, well-spaced type, with black and white illustrations, in which Clelia, Fabricio, Sanseverina and Mosca, the fresh, humid, sometimes transparent landscape of the Padana valley, the narrow cell where the young Del Dongo learned to be happy, would appear”.

The above paragraph is the beginning of the one Graziella Pogolottie wrote for Stendhal’s work Set in Napoleonic Times, published by the Cuban Book Institute in 1971, in the unforgettable Biblioteca del Pueblo collection, where great novels of universal literature were preceded by texts by notable Cuban authors, prologue duos and enduring titles: Alejo Carpentier and La montaña mágica; Eliseo Diego and Orlando; Pablo Armando Fernández and Cumbres borrascosas, to cite three examples.

In this exercise, her work has had a happy performance, as pointed out in the aforementioned collection. In an interview included in my book of conversations with thirteen Cuban writers, El sabor del instante (Ediciones Holguín, 2016), she has warned: “The prologue is important to the extent that it opens new and unsuspected perspectives to the reader, who sometimes reads it before and sometimes after encountering the work. Its effectiveness is given to the extent that it is, at the same time, an invitation and a suggestion”.

It is also worth remembering that of Gargantua and Pantagruel, by Francois Rabelais, also in that collection, an invitation to that great book of the sixteenth century: “He wrote the unlikely adventures of his two good giants as a man of his time, immersed in the ideological struggle of the century, in difficult times when a translator of classical Greek texts could be led, for that fact, to the stake. (…) A student of classical languages and literature, a doctor by profession, a writer, Rabelais followed all paths”.

Another example of Graziella’s mastery is Confessions of an Italian, by Ippolito Nievo, a forgotten 19th century author with a sparkling life between 1831 and 1861 – a fighter for the independence and unification of Italy in the ranks of the hero Giuseppe Garibaldi, poet and journalist, who wrote an “imaginary autobiography” that led him to live to the age of eighty, when in reality he died at the age of thirty, after the shipwreck of the steamer in which he was traveling in his independence efforts from Sicily to Naples.

Published in 1981 -also in Biblioteca del Pueblo-, Graziella Pogolotti invites to those Confessions… from the figure of its protagonist, “observer and participant of the events, he joins as one more to the conspiratorial groups, he is a soldier in times of war, administrator when the hour of combat ceases (…) As it is about an old man who pretends to make a final balance of his life, there are also moral reflections (…) marked some by the seal of the time, but many others surprisingly lucid”.

Moreover, his essays collected in El ojo de Alejo (Ediciones Unión, 2007) ratify his passion for Carpentier’s work -whom he knew since childhood: his father was a friend of the writer-. The contexts that govern the narrative structures of the great novelist, warn of “the insatiable curiosity, that virtue proclaimed in one of his chronicles? -as Graziella notes, since his work highlights the pleasure of the “seeker of communicating vessels between music, visual arts, theater and literature”.

In her memoir Dinosauria soy (Ediciones Unión, 2011), she points out that “happiness exists, as long as we are capable of recognizing it and capturing it in the unrepeatable present of its sudden appearance to preserve it in our memories with the warmth of its burning ashes”. Such an assertion is well worth remembering that “both the teacher and the critic, and everyone who has to do with literature, must strive to protect the fact that reading is a pleasure”. This is confirmed by Graziella Pogolotti and the attraction of the prologue.

In her memoir Dinosauria soy (Ediciones Unión, 2011), she points out that “happiness exists, as long as we are capable of recognizing it and capturing it in the unrepeatable present of its sudden appearance to preserve it in our memories with the warmth of its burning ashes”. Such an assertion is well worth remembering that “both the teacher and the critic, and everyone who has to do with literature, must strive to protect the fact that reading is a pleasure”. This is confirmed by Graziella Pogolotti and the attraction of the prologue.

- Maggie Mateo returns as a storyteller - 21 de May de 2025

- Farewell to Mario, Don Miguel’s disciple - 16 de April de 2025

- The savage detective and the unsubmissive translator - 7 de April de 2025