It was a day of radiant sunshine, but the heat that enveloped Cuba on that December 22nd, 1961, was not just tropical heat. It was the heat of emotion, of a victory forged in the will of a people. In the plazas and bateyes, people gathered. Not for a celebration, but to witness the end of an era.

The voice of Fidel Castro, resonating in every corner, declared the unthinkable: “Cuba is a Territory Free of Illiteracy.” The words flowed like a balm upon the souls of millions who, until then, had lived in the shadows of ignorance.

Faces weathered by the sun and labor were now illuminated with tears of joy. It was not just the learning of letters and numbers. It was the recovery of dignity, the key to a world of knowledge that had been denied them for centuries.

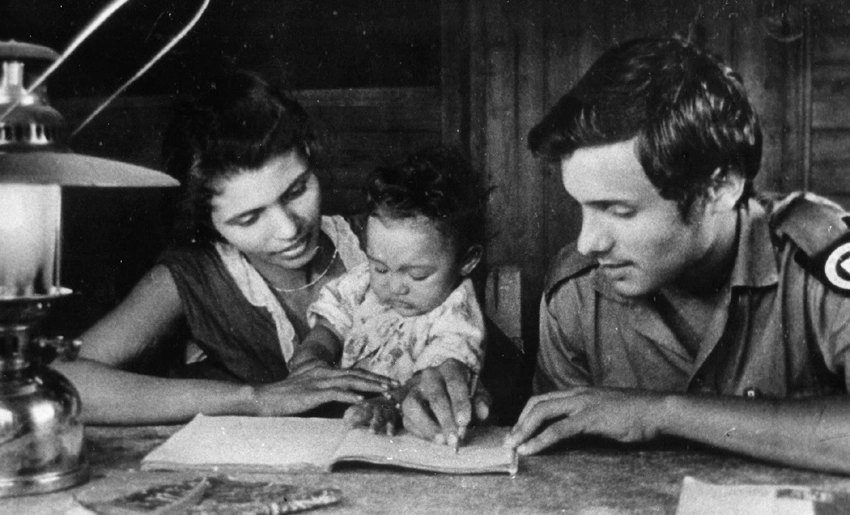

Thousands of young faces, illuminated by the conviction and weariness of an epic battle, gazed toward the grandstand. They were the soldiers of a unique war, whose battlefields were the huts, the coffee plantations, and the most remote corners of the island. Their weapon: a pencil and a primer. Cuba was not celebrating a military victory. But a conquest of the spirit: it was declaring itself a Territory Free of Illiteracy.

Also to understand the magnitude of the jubilation that December, one must go back to the preceding years. After the triumph of 1959, the nascent Revolution encountered a stark reality. Almost a million compatriots could neither read nor write. The inequality was abysmal: in rural areas, illiteracy reached 47.1% of the population. While in the cities it was 11%. More than 600,000 children lacked access to education.

Before the United Nations General Assembly in September 1960, Commander-in-Chief Fidel Castro made a promise that many considered a pipe dream. Cuba would be the first country in the Americas to eradicate illiteracy in just one year. Thus, 1961 was proclaimed the “Year of Education.”

Moreover to wage this battle, an army unlike any seen before was organized. The “Conrado Benítez” Brigades were formed, comprised of more than 100,000 young students. Many of them barely teenagers, who left their homes and cities. They were equipped with a uniform, a blanket, and the symbol that would forever identify them. An oil lamp to light their nights of study in the countryside.

The campaign was a work of the entire nation. Alongside these brigadistas marched 178,000 community literacy teachers and 30,000 workers from the “Fatherland or Death” Brigades. Who maintained their salaries while teaching. The method, outlined in the primer “We Shall Overcome,” combined literacy instruction with the principles of the Revolution. It was an unprecedented mobilization, where a child could become his father’s teacher, and a worker could become his own son’s student.

Futhermore the undertaking was not without danger and sacrifice. Young people like Manuel Ascunce Domenech and his student Pedro Lantigua were murdered by counterrevolutionary groups. Their martyrdom, and that of others, added a profound sense of commitment and sorrow to the campaign.

Thus, December 22nd arrived. The plaza was filled with literacy volunteers. One of them, Lilavatti Díaz de Villalvilla, would recall decades later: “The victorious gathering in the Plaza de la Revolución was a fitting end to that great battle… Afterward, joy overflowed the plaza, an unforgettable jubilation when the flag proclaiming Cuba a Territory Free of Illiteracy was raised.”

In his speech, Fidel Castro summarized the feat: “We are going to raise the flag with which the people of Cuba proclaim to the world that Cuba is now a Territory Free of Illiteracy.” He acknowledged that the task seemed impossible, “unless that task was undertaken by a people in revolution.” The final figure confirmed it: 707,212 people had learned to read and write in a single year. Reducing the national illiteracy rate to 3.9%, the lowest in Latin America at that time.

To honor the protagonists of that victory, it was decided that December 22nd would be celebrated as Teacher’s Day. Not only as a commemoration, but as a living principle. In Cuba, to educate is “to deposit in each person all the human work that has preceded them,” as José Martí taught.

More than six decades later, the echo of that victory continues to resonate. Every December 22nd, Cuban schools pay tribute to their teachers. The occasion is also used to recognize outstanding educators with awards. Such as the Frank País Order and the Distinction for Cuban Education.

So the commitment to education transcended borders. From that experience was born the “Yes, I Can” method, a literacy program endorsed and awarded by UNESCO. Which has taught more than 10.6 million people in 30 countries to read and write. The feat of 1961 demonstrated that mass literacy was possible and laid the foundation for a universal and free education system recognized worldwide.

The chronicle of that December of 1961 is not just the story of a campaign. It is the chronicle of how a people, mobilized by a common ideal, managed to overcome centuries of darkness. It is the story of young people who, with a lamp in one hand and a primer in the other, illuminated the path so that Cuba could, for the first time, write its own destiny.

As Fidel declared years later: “There is something harder than… marble or steel… what can never be destroyed is the page of history that you have written.” A page that is reread with the grateful murmur of a people who learned to be free because they first learned to read.

Cuba not only eradicated illiteracy; it sowed the seeds of hope. It demonstrated that the will of a people, when united in a common purpose, can move mountains. Since then, every December 22nd, Cuba celebrates Teacher’s Day. Honoring those young brigadistas who, with their lanterns and books. Illuminated the path toward a more just and equitable future. A future where the light of knowledge would never again be a privilege, but a right for all.

By: Daimy Peña Guillén

- Holguin Clinic Improves Orthodontic Treatment Despite Impacts from the U.S. Blockade - 6 de February de 2026

- French Prime Minister acknowledges consequences of the US blockade - 5 de February de 2026

- Wetlands Protected in Holguin - 5 de February de 2026