Ernest Hemingway began his literary career in journalism. Certain characteristics of his style—economy of means, the brevity of the typical sentence, the power of synthesis, an observant eye, descriptive precision, and sobriety in using adjectives—were acquired, to a certain extent, through his practice of journalism.

Hemingway began his career as a reporter at the Kansas Star newspaper. This apprenticeship lasted seven months: in 1918, Hemingway joined the Red Cross and left for Europe, where World War I was entering its final phase.

That time at the Star was extremely useful to him: he would canvass experienced reporters, soliciting their criticism and advice. He was possessed by a burning desire to learn to write well, as every good newspaper professional should feel.

The Kansas diary had a stylistic pattern: declarative sentences, brief opening paragraphs, and rationalization of adjectives, which he assimilated. Upon returning from the war, he began working for The Toronto Star. Hemingway’s association with this newspaper lasted until he returned to Europe as a correspondent in 1923. Hemingway included many of his press dispatches, as short stories, in his early books.

Between 1920 and 1950, Hemingway’s journalistic work was published in the Toronto Star, where he wrote 154 articles. He wrote 31 articles for Esquire magazine, while he did 28 reports and interviews for the North American News Alliance (NANA) news agency. He also contributed to Collier’s magazine, where he was the European bureau chief at the end of World War II. Holiday, True, Look, and Life magazines all received contributions from this great reporter.

His main goal, at that time, was the utmost journalistic synthesis, and so he described only what was necessary to eliminate the superfluous. He would later say that it was enough to recall a true detail, something that impressed him, and the evocation of a single aspect would be enough for the reader to piece together the complete picture in their mind.

Upon leaving for Europe, Hemingway sent his chronicles at a rate of two per week. He met Max Beerbohm, the grumpy English cartoonist, who preached against the evils that journalism inflicts on writers. Apparently, this sermon made some impression, and upon his return to Paris, he devoted himself more consistently than ever to writing cartoons and poems.

The success of his novel The Sun Set and his entry into the literary world as a promising young figure concluded his first period as a journalist. From then on, his chronicles would take on a different, more relaxed, and more mature and worldly air.

In December 1934, he published “Old Journalist Writes: A Letter from Cuba” in Esquire magazine, in which he criticized reporters who write opinionated stories and didn’t bother to observe the events. He argued that editorialists should take the time to verify what they really knew about the mechanisms, theory, and background of the phenomena they were writing about.

He later confessed that the hardest job in the world is to write honest and direct prose about human beings, because first you have to know the subject and then you have to know how to write about it, and both take a lifetime to learn.

In 1937, Hemingway signed a contract with the NANA news agency to cover the Spanish Civil War. On April 11th, he reported on the shelling of Madrid and described the death of an elderly woman returning from the market whose leg was severed by an explosion. All of these dispatches are models of war reporting: dry, sober, based on precise facts, with the necessary observations to evoke the atmosphere and the necessary verbs to recreate the action.

In 1941, Ralph Ingersoll, editor of the New York newspaper PM, hired Hemingway to report on the Sino-Japanese War. Hemingway left for China in January. In an interview with Hemingway, Ingersoll said that his reputation as a novelist had somewhat diminished his reputation as a journalist and war correspondent, as he was considered a leading expert on military affairs.

In these dispatches from China, there is a noticeable variation in content and style. Hemingway is no longer the novelist, no longer the stylist of English prose, no longer the young narrator attempting synthetic experiments with words: he is now a political-military specialist. His articles are filled with military terms: logistics, fortification, vulnerability, destructive capacity, divisions, and tactics.

Hemingway writes like a connoisseur because he is now more analytical in his assessments, predictions, and judgments. He is no longer, as in his earlier chronicles, isolated from his political context.

His report on this action, titled “Journey to Victory,” was published in Collier’s on July 22nd and is the longest piece of journalism he ever wrote. His chronicle “London Fights the Robots” was chosen as one of the best ever written about World War II.

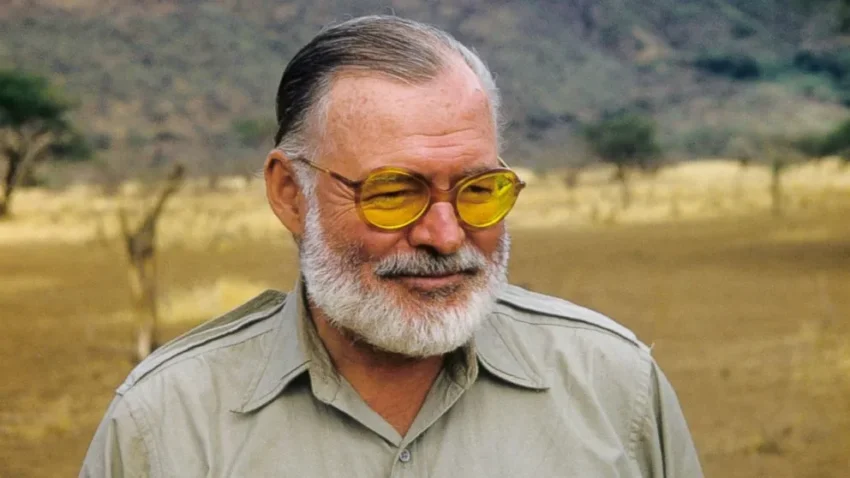

After WWII, he returned to Cuba and wrote the same type of material he had previously submitted to Esquire magazine, about fishing and hunting, for Holiday magazine. In 1954, he wrote “The Christmas Gift” for Look magazine, about one of his safaris during which he suffered a plane crash, leaving him presumed dead for several days, and which gave him the strange pleasure of reading about his supposed death.

His last report, “A Bloody Summer,” was written in 1960 for Life magazine and consisted of an account of the duel between bullfighters Luis Miguel Dominguin and Antonio Ordóñez during a bullfighting season in Spain.

Despite his long association with journalism, and his mastery of it, Hemingway ended this long-standing relationship in divorce. In September 1956, he wrote in Look magazine: “All excursions into journalism, broadcasting, propaganda, and film, however grandiose they may seem, are destined to end in disillusionment. To put our best into these forms is folly… the nature of this kind of work is perishable… the true function of a writer is to produce a masterpiece; no other work is transcendent.”

But he demonstrated that every great journalist can also be a great writer, and that there is no difference when one writes literature from journalism, with mastery of technique and abundant in the experiences of an intense and cultured life like that of this great man.

- When eating pizza doesn’t lead to Rome - 18 de January de 2026

- The Fright of Tuesday 13th: Between Religion, History, and Tradition - 13 de January de 2026

- The Pictorial World of the Gelpi Brothers - 12 de January de 2026