Apart from his elective affinities, nothing better than Goethe‘s term. With poetry, essays and narrative to intersect his territory of creation. For more than twenty–five years a writer from Holguin has made literary translation, to put it with the title of a legendary poem by Eliseo Diego. “The place where one is so good“.

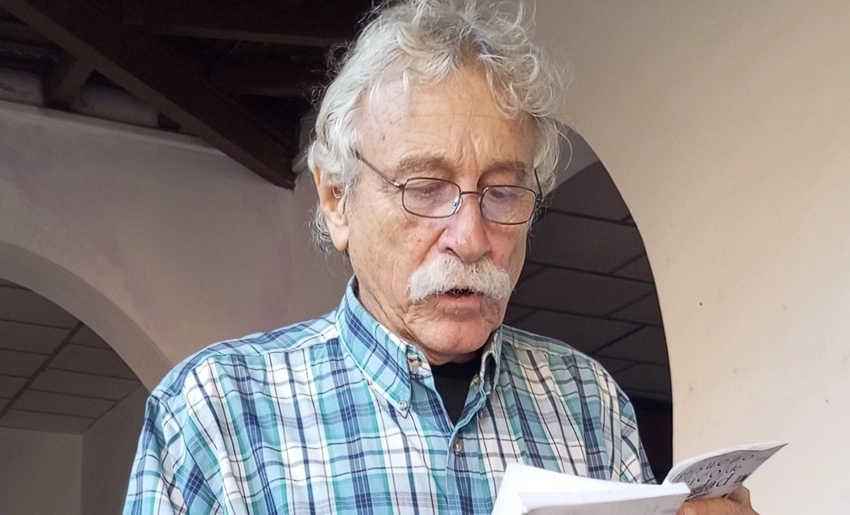

Manuel García Verdecia was not only satisfied with his passion for the English language as a teacher. Both in secondary and university education. But also set out to bring those voices to the possessions of his native language.

A poet who relates the personal and the collective with gentleness of writing and insight of observation. Anchored in memory and its vicisitudes. An essayist who opens up new readings in highly renowned areas such as those of Gastón Baquero, Alejo Carpentier and Lisandro Otero. To cite three examples; and narrator who delves into the most unexpected feelings.

Manuel’s translations, published in Cuba, constitute one of the most striking areas of such performance. And can be placed with great value far beyond the insular sphere. It is worth remembering ‘The Prophet’, by Kahlil Gibrán. ‘The Disturbing Muses’, by Sylvia Plath; ‘Locas, locas mujeres’, by Anne Sexton.

‘To the Lighthouse’, by Virginia Woolf, ‘Meridiana’, ‘The Temple of My Spirit’, and ‘The Secret of Joy’, by Alice Walker… These are some examples, published by Editorial Arte y Literatura, Ediciones Holguin, and Editorial Oriente, which have placed in the hands of Cuban readers a range of works and periods.

It is also noteworthy to point out another translation by Manuel, but from the French language to ours. An extremely suggestive incursion of one of the great poets of the twentieth century. Saint-John Perse, and ‘The Sea Like a Sky’, in Ediciones La Luz. Adds with outstanding moments of the work of the famous author born on the Antillean island of Guadeloupe, and Nobel Prize in Literature 1960.

In his book ‘Versions and Diversions’, a selection of poetic translations made by Octavio Paz, Nobel Prize for Literature 1990. The author points out in his introduction that it is “… carpentry, masonry, watchmaking, gardening, electricity, plumbing in a word, verbal industry. Poetic translation requires the use of resources. Analogous to those of creation only in a different direction.” In this direction, a trio of works that illustrate such a commendable task are affirmed. Particularly in the shadow of this year’s Cuban Book Fair: this is demonstrated by Manuel’s three W’s.

How would you break down, based on your experience, the postulates established by the great Mexican poet?

“I consider translation as a work of co–creation. The book that I give to readers has not existed before, but a version, albeit a primitive one, in another language and with other references. Translation is like repentismo: another author suggests a forced foot and from him I have to compose the text. The author gives me a subject, some characters, a context, certain implications of significance. I must apprehend that and redo it, in the most effective way possible, from another thought, another culture and another language.

“The fact of transcribing it into another language makes it a different work, because what the translator achieves depends a lot on his imaginative and cultural capacity. Think about this: I have to translate the word “bread“, but how many shapes, flavors, smells, qualities, can bread have?

Jorge Luis Borges, also a translator of that great poet. Said that “Whitman recalls medieval canvases with many characters. Some haloed and preeminent, and declares that he intends to paint an infinite canvas. Populated by infinite characters, all with their halos.”

How did you deal with the demarcation of such a complex and varied fabric?

“Whitman is the poet of democracy and transcendentalism, which is why his work teems with beings that the author seeks to set in motion to reproduce that world where we are all creatures of God in equal conditions and meaning. As with every author, one is obliged to study his time, his living conditions, his intellectual intentions, his expressive manners, in order to face his work. So one is almost forced to live a little “Whitmanianly,” in this case, or “Woolfianly“ in another, etc.

“You can’t perceive the same thing as another person if you don’t place yourself in your own field of vision. Martí said, very appropriately, that “to translate is to transthink” and I would say “transver” as well. It is not only a matter of reading and understanding a work, but of feeling, incorporating, the world of meanings that the original author tried to express. That confrontation that you tell me about was only possible by studying a lot to place myself in Whitman’s time-space and from there utter his renewing howl.”

“Whitman’s language is a contemporary language,” Borges added. How much does such an assertion contribute when translating ‘Leaves of Grass’?

“Yes, Whitman inaugurates modernity in American poetry, not only because of his way of seeing the world and his fellow men, but also because he democratizes the language. He writes how New York typographers, Virginia farmers, Mississippi sailors, comrades-in-arms in the Civil War spoke…

“It assumes the orality of its moment and, through its finesse and high sensitivity, gives it the necessary tension to illuminate multiple meanings. After all, that is what poetry is: to be able to say what often evades our ability to enunciate. This brings the author’s world closer to ours, as it makes it more contemporary and, therefore, more expressible.”

Mario Vargas Llosa, Nobel Prize in Literature 2010, points out in his essay on ‘Mrs. Dalloway’ that “the life-giving transformative power of Virginia Woolf’s prose fills those pages with charm and mystery”.

How did you manage to preserve such assumptions in their ‘journey’ from English to Spanish?

“How did I do it? By two main means: study and will. I repeat something I have already said: in order to translate a text in the most effective way possible, one is obliged to “look” with the eyes of the author. It is a doubly difficult matter, since it is not only a question of another language and another culture, but also of a generic condition that imprints sui generis characteristics on the text.

What difficulties can a novel like ‘The Color Purple‘, set in the conflicts inherited from slavery in the south of the United States, offer when it comes to bringing the interiorities worked on by Alice Walker into Spanish?

“We return to the need to put ourselves “in the shoes of the other“. In order to convey a vision, the most appropriate and truthful of the world that Alice Walker relates, I had to make an effort, not only to see it as closely as possible to how she sees it, but to understand it as she understands it.

The author comes from an environment where her indigenous and African–American ancestors intersect, as well as her condition as a woman, for whose three traits her peers have suffered oppression, violence and oblivion. It is necessary to understand these issues in order to sensitively provide the universe of feelings, values, frustrations, boldness, dreams, that she seeks to present.

How much does it favor a literary translator to also be a poet, and how can both tasks be intertwined?

“I begin by telling you that, in fact, a translator has something of a poet and I am not referring strictly to the one who makes verses, but to the creator through the word. It is someone who wants to do work, even if it starts from someone else’s idea. If not, he would be a mere reader. Of course, the fact that the translator has developed the craft of poet means that this person has perceptions, a sensitivity, a faculty for linguistic creation that, by becoming a kind of alter ego of the original author, he has greater intellectual and technical facilities to achieve his purpose.

“However, there is something that I never tire of pointing out: although being a poet facilitates the work of translation, being a translator is a very effective school for writing, since one is obliged to get into the mental mechanisms of the other author, to see life with different eyes and to realize how the other author solves the complex problems of verbal creation. So there are gains both ways.”

After Whitman, Woolf and Walker, which authors or titles are in the pipeline for future translations?

“Oh, friend! You are an accomplished reader and you know that for this there is no greater temptation than a library. And the reader, usually, does not want to keep the treasure found, he wants to share it, so that everyone knows what gold and precious stones all those pages hide. So if time and possibilities favored me, I would translate everything we still don‘t know about other literatures.

“But as we must be sensible, and even more so because of these times of various precariousness that we are going through, we are obliged to be cautious. So there is a novel by Alice Walker that it would be good to translate into Spanish, ‘The Third Life of Grange Copeland’, which rounds off what we already know from other novels of his. Or a version of ‘Dubliners’, by Joyce, which shows so much about human relationships, or the stories of Chaucer or those of Faulkner, with so many surprising discoveries, or the poetry of Robert Frost or that of Maya Angelou, or the essays of Aldous Huxley, so essential… In short, let’s hope for God for the time and for the publishers for the opportunities.”

By: Eugenio Marrón Casanova

Translated by Radio Angulo

- Challenges of Monetary Stabilization in Cuba - 13 de February de 2026

- Medical Equipment in Holguin Guaranteed to Be in Operation - 12 de February de 2026

- Aid Arrives in Cuba from Mexico - 12 de February de 2026