It was a November morning in the mid-seventies, in the offices of the Cinemateca de Cuba in Havana, on the eve of the Soviet Film Week: two young twenty-somethings from the East – one from Manzanillo and the other from Holguin – in the shadow of readings and films that sponsored the routes to follow of both, they were talking with that cordial and generous prince of the seventh art in a Cuban key that was Héctor García Mesa, director of the prestigious entity. It was there the invitation that would be a great gift, a real turning point for writings and reflections to come.

“I am waiting for you this afternoon at five o’clock to accompany me to Andrei Rublev’s premiere.” It was the phrase for a banquet that, over the years, ended up being the greeting every time we met, almost a Masonic affinity; evoke some fragment of Andrei Tarkovsky’s film that we had seen in the Chaplin room, the images as if they had just come out of the filming, the story of that painter of icons in medieval Russia – we both agreed that it was not only a cinematographic epic, but also a great novel – that illuminated our paths so much.

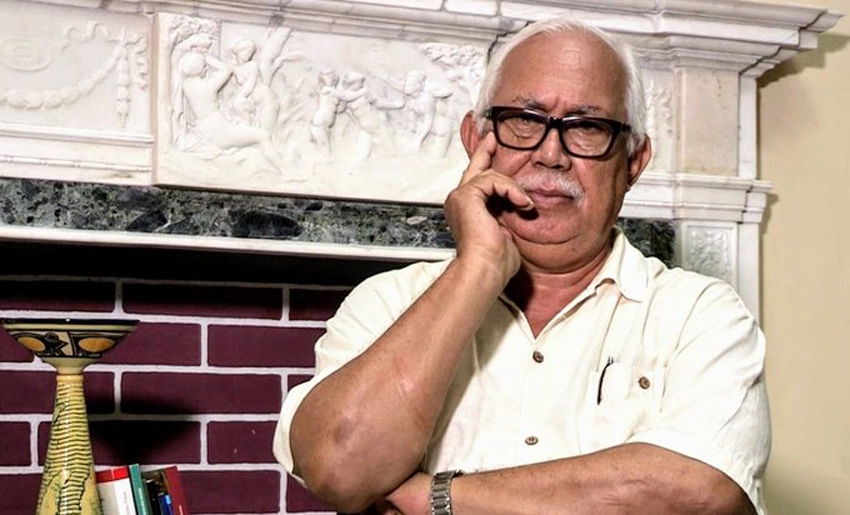

There is a phrase by Pablo Neruda that assails me when I sit down to write these lines, when on one occasion, when asked how he would approach a subject related to his affective impression, the poet replied: “I never know where to start, if with the jacket or with the heart.” This is what happens now to the author of this column, after the very sad news of the death of Francisco López Sacha, writer, professor and manzanillero —the demonym, more than a colophon, was in his case the key to his well-defined intimacy—, evoking the traits of a mutual sympathy that is demarcated in little more than fifty years.

Literature and cinema were always the touchstone that opened the doors to dialogue in each encounter; and so it jumps like a hare, just at this moment, one afternoon at the end of the nineties, in the Holguin Library on the verge of a conversation, when, after greeting and remembering some passage from Andrei Rubliev —our endearing ritual—, he blurted out to me like an actor who goes on stage: “You have to look for a novel that you haven’t discovered, with maps and everything, The English Patient, by a writer from Ceylon, Michael Ondaatje, you’ll see…”. Only then was the film about to come out.

“Like an actor who goes on stage”, I have pointed out, and it is one of the conditions that nourish the remembrance of Sacha, under the protection of a loquacity as consummate as vigorous, holy and a sign of his performance as Professor of History of Theater at the Higher Institute of Art. In this, his mastery of intonation, the oral heritage, the figure gravitating on the slightest crack of space, his gestures, the movement of his hands had a decisive impulse… “You are like Vittorio Gassman in il sorpasso”, he said in allusion to that film that we praised so much in Italian cinema of the sixties.

To the above was added a natural sympathy, an energetic memory that moved gracefully through the most dissimilar areas, whether it was the songs of The Beatles, the universal theater —fragments of A Doll’s House or Uncle Vanya, two examples among many—, anecdotes of the independence struggles of 1868 in their most precise spaces —I retain a distant day in Bayamo during a literary conference, when, together with Pocho Fornet, in front of the birthplace of Francisco Vicente Aguilera, I witnessed an unforgettable portrait of the patrician, Sacha as a verbal painter in front of his canvas—… Inexhaustible remembrances.

Both conditions, natural sympathy and energetic memory, confirm the unfolding of his course as a writer, the various scales of acuity, affection, longing, intuition, which he could combine, from his initial novel, El cumpleaños del fuego —which integrated at the beginning of the eighties the notorious “narrative forecast” for the decade, established by Ambrosio Fornet, together with projects by Jesús Díaz, Miguel Mejides, Senel Paz, Alejandro Querejeta… —, going through short stories, to that autobiography in other ways and almost very personal learning novel, Prisoner of Rock and Roll.

It is in that title, almost to be heard as a vinyl record of the old days – revived with its return to the markets of the world – that the most flattering requests of the boy who imitated Paul Anka, the one who dreamed of being an extension of the Liverpool quartet, the Bob Dylan connoisseur, are demarcated. circumstances that —to say it with two chapters of that book— endorse “the sweet bird of youth” and its flight in “the magic ring of time”: a walk between voices and electric guitars first, and then the most varied instruments, in favor of a fulfilled devotion.

These conditions – youth, time – are hallmarks that run through his narratives, where his craft reaches a fullness that is sustained by the most seductive mastery, the in-depth knowledge of Boccaccio, Chekhov, Quiroga, Borges, Cortázar, Hemingway, Rulfo, Cardoso, Labrador Ruiz and his compatriot Luis Felipe Rodríguez (among so many storytellers read from a very young age). the passion for a knowledge that he knew how to convert, many years later, into a fortune of teaching in chairs and events, the spell of his conferences and his classes, any dialogue wherever it went: inexhaustible pleasure.

Like any reader of Sacha, I remember not a few of his stories and his characters, those that notice the development of a prodigious fabulist, a vocation to encounter the best of the art of storytelling, his very personal imprint in which remembrance and tenderness converge, under the frond of the circumstances already mentioned, the probable and the unusual, grace and compassion, the pertinent and the unexpected, the past and the present, in favor of the instant of the story told being always the determining thing that the word can preserve: all times time.

I must point out that although he ventured into the novel —the one already mentioned, plus I’m going to write eternity, and some other unpublished one—, the best definition for Sacha is that of storyteller, literary royalty to which he belongs in the insular sphere, and beyond.

There is to confirm it, among others, Figures on the Canvas, an unforgettable meeting of Emilio Zola with the very young José Martí, a premiere night in Paris under the roof of The French Comedy, an exemplary piece that stands out for its meticulous and delicate verbal goldsmithing, a rapture of wit, one of the most moving stories of twentieth-century Cuban literature.

Almost at the end of the three-hour journey of Andrei Rubliev, when he meets little Boriska, the son of the blacksmith who moulded bells, he says: “We will continue to work together, you will cast bells, I will paint icons”. Thus, every time we met, the presence of that film that had accompanied us since a distant afternoon in the Cinemateca de Cuba returned—”We owe that gift to Héctor García Mesa, don’t forget it,” he told me—and it was our best greeting: Either I would melt bells and he would paint icons, or vice versa. That’s how I say goodbye to him, owner and lord of verba grande, Sacha on stage.

By: Eugenio Marrón Casanova/Translated by Radio Angulo

- Installation of Photovoltaic Systems in Rural Communities in Holguin - 19 de January de 2026

- 39th City Salon Opens in Holguin - 19 de January de 2026

- Habanos Festival Among Cuba’s Most Important Tourism Events - 19 de January de 2026